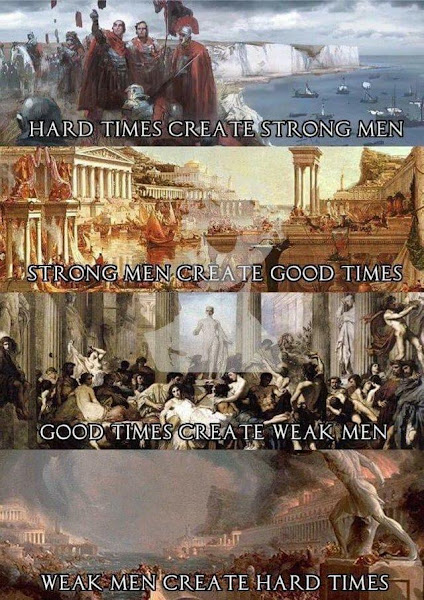

One sees this bullshit around a lot:

Historian Bret Deveraux calls shenanigans briefly in Foreign Policy and at length on his blog.

I’m choosing the Fremen — and really the Dune series more generally – to stand in for a particular set of oft-repeated historical ideas and assumptions. It is not one idea, so much as a package set of ideas — often expressed so vaguely as to be beyond historical interrogation. So let’s begin by outlining it: what do I mean by the Fremen Mirage? I think the core tenants run thusly:

- First: That people from less settled or ‘civilized’ societies — what we would have once called ‘barbarians,’ but will, for the sake of simplicity and clarity generally call here the Fremen after the example of the trope found in Dune — are made inherently ‘tougher’ (or more morally ‘pure’ — we’ll come back to this in the third post) by those hard conditions.

- Second: Consequently, people from these less settled societies are better fighters and more militarily capable than their settled or wealthier neighboring societies.

- Third: That, consequently the poorer, harder people will inevitably overrun and subjugate the richer, more prosperous communities around them.

- Fourth: That the consequence of the previous three things is that history supposedly could be understood as an inevitable cycle, where peoples in harder, poorer places conquer their richer neighbors, become rich and ‘decadent’ themselves, lose their fighting capacity and are conquered in their turn. Or, as the common meme puts it:

Hard times create strong men.

Strong men create good times.

Good times create weak men.

And weak men create hard times.(The quote is originally from G. Michael Hopf, a novelist and, perhaps conspicuously, not a historian; one also wonders what the women are doing during all of this, but I have to admit, were I they, I would be glad to be left out too).

[⋯]

This complex of ideas is what I phrase as the Fremen Mirage, and as you might imagine from that word ‘mirage,’ there are real, gaping problems in this vision of history. I’ve picked the Fremen to stand in for this idea in part because — being a fictional people — they are unconstrained by the real world messiness of actual societies. Instead, Frank Herbert quite clearly intends the Fremen to be a sort of purified form of this trope, the hardest people from the hardest conditions; they’re even presented as being more extreme than another example of this same trope, the imperial Sardaukar, who also indulge in the same ‘hard men from a hard place’ idea. Moreover, Herbert plays out this cyclical vision of history in the books, with the going-soft (slowly) Sardaukar being no match for the hard-ways Fremen and the latter – despite a near total lack of modern military or industrial infrastructure and what should be a crippling manpower disadvantage — spreading out and defeating all of the ‘civilized’ armies they encounter (with attendant worries that they will will become ‘soft’ and thus weak, should their planet, Arrakis, be made more habitable).

Now, the way this trope, and its contrast between ‘civilized’, ‘soft’ people and the ‘uncivilized’ ‘hard’ Fremen is deployed is often (as we’ll see) pretty crude. A people — say the Greeks — may be the hard Fremen one moment (fighting Persia) and the ‘soft’ people the next (against Rome or Macedon). But we may outline some of the ‘virtues’ of the ‘hard men’ sort of Fremen are supposed to have generally. They are supposed to be self-sufficient and unspecialized (often meaning that all men in the society are warriors) whereas other societies are specialized and overly complex (often to mean large parts of it are demilitarized). Fremen are supposed to be unlearned compared to their literate and intellectually decadent foes. Fremen society is supposed to be poor in both resources and infrastructure, compared to their rich and prosperous opponents.

The opposite of Fremenism is almost invariably termed ‘decadence.’ This is the reserve side of this reductive view of history: not only do hard conditions make for superior people, but that ‘soft’ conditions, associated with complex societies, wealth and book-reading weenies (read: literacy) make for morally inferior people who are consequently worse at fighting. Because we all know that moral purity makes you better at fighting, right? (My non-existent editor would like me to make clear that I am being sarcastic here, and it is extraordinarily obvious that moral virtue does not always lead to battlefield success.)

[⋯]

... the idea at the core of the Fremen Mirage is that the Fremen are militarily stronger in a general sense. If I may lean on a sports analogy, we would not call a team ‘better’ if they lost 98 games but happened to win the last 2. The question is both the ratio of victories to defeats, and the impact of those results. And that’s why the march of the state and of farming is so instructive: we can see the same process repeat itself, in a wide variety of areas, over very long periods of time, with what must have been many hundreds if not thousands of small wars. And it is quite clear from that evidence, that at the dawn of civilization, it was the least Fremen societies who tended to win the most.

A bit related

A little history of how Iceland changed from a violent to non-violent society:

So, for those from countries where, paradoxically, routinely arming police makes people feel safe, a short history of Iceland’s path from being one of the more brutal and violent nations in Europe to being a largely pacifist one.

The Vikings were not known for their pacifism. The voting system for Iceland’s Althing, for example, was proxy combat. Effectively, you assessed which side, for or against a proposal, was likelier to win in combat. Recounts or challenges to that assessment meant doing the actual combat and seeing which side won. And, yeah, that could mean that having a noted sociopath and former mercenary like Egill Skallagrímsson on your side could result in it winning even though it had fewer numbers.

Our predilection towards violence continued until internecine violence escalated to such a point where the country became completely dysfunctional, our resources depleted, and we lost our independence to Norway in 1262-4. Then Norway lost their independence to the Danish and once the Danish took over things steadily got worse. The Danish ran monopoly and starvation policies in Iceland, where each part of Iceland was controlled by a regional governor (sýslumaður), who operated on behalf of the Danish crown, and who had legislative, executive, and judicial powers. The authorities were effectively free to loot their region at will. Most of the violent massacres in Iceland’s history after we lost our independence were done at the direction of these regional governors.

[⋯]

Combined with Iceland’s tendency towards natural disasters — weather, volcanos, and earthquakes — and the ruling authority’s refusal to build any infrastructure to deal with any of it, meant that Icelanders died a lot. Like, a lot.

[⋯]

It should not surprise anybody then that the Icelandic independence movement was largely pacifist and non-violent. If the Danes threatened violence, like by sending a representative of the crown with an armed guard to demand that you ceded your demands of independence, you stood your ground but didn’t raise your fist. “We all protest.”

We attained self-rule in 1918 and from the start our constitution called for both pacifism and neutrality ….

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.