Posts on this subject are obviously fraught, so first:

-

I keep an index of resources

-

the moral question is simple:

Palestinian liberation is right & necessary

-

the history is complicated:

hence this post attempting to dispell many common misunderstandings

-

the praxis is complicated:

antisemitic entryism into the movement for liberation is subtle, pervasive, and unacceptable

This post was originally written in 2021, though I have made an ongoing series of refinements and additions since then

Because of the [2021] horrors undertaken by the state of Israel, a friend said something characteristic of a lot of American lefties who have had to un-learn both pro-Israel propaganda and US propaganda about our own history:

Israel is exactly a parallel of the US. It’s a settler-colonial state that displaces and claims the territory of the people who were there before [⋯] That’s also why the US supports Israeli actions so much.

I got long-winded in my frustrated reply, and that led to this short history of the Israel-Palestine conflict, in which I try to iron out some common misunderstandings.

US support for Israel

First I must dispense with an obvious canard. No, the US does not support Israel out of some weird settler colonialist solidarity. There are a few big factors behind strong US support for Israel:

-

The US military is very interested in being able to intervene in a lot of places in Israel’s neighborhood and it helps to have an ally who will let US planes land and refuel on their airbases.

-

Republicans support Israel’s policies because they are in the grip of Evangelicals who believe that Israel is an integral part of realizing Biblical prophecy. (I would think that one would want to devote our foreign policy to preventing Armageddon, but what do I know?)

-

Democrats support Israel’s policies because they are in the grip of the hardline Israel lobby whom liberal Jews have been too feckless to purge from the coalition.

-

Americans on both sides of the aisle are prone to anti-Muslim bigotry which sharpened in the wake of the 11 September 2001 terrorist attack, leading to a reading of Israel as a natural ally against the villainous Arab world, and a reading of Arab Palestinian resistence to oppression by Israel as nothing other than villainous Muslim terrorism.

The USA is different

The other part of my friend’s comment — the question of Israel’s settler colonialism — requires unfolding a lot of history. At the bottom line, Israel is the result of a settler colonial project and that project is ongoing in the present crisis, but analogizing it to the history of the US is irresponsibly misleading.

Prior to the founding of the USA in the Revolutionary War and its aftermath, the British colonies in North America starting even at Plymouth Rock were engaged in settler colonialism: seizing land with the intention to make it their own for every following generation, with total disregard for the indigenous people of the continent. By the time of the Revolution what would become the US had more than a century of expansionist settler colonialism with an overt program of total genocide to establish British sovereignty over territory; the program of genocide continued through the closing of the frontier, a legacy which is alive in the present day.

Israel’s history is bloody and ugly but it is very different.

Zionism before Israel

The Zionist project can be seen as beginning with the First Zionist Conference in 1897, when what is now Israel was still part of the vast, weak Ottoman Empire. It is important to understand that the Zionism conceived then did not seek to establish the state of Israel as we now have it. The Conference in 1897 defined their project thus:

Zionism aims at establishing for the Jewish people a publicly and legally assured home in Palestine.

In this we can see how Zionism is indeed an ethnic nationalism but not quite what one might naïvely imagine from the succinct description “Jewish nationalism”.

First, the 1897 statement shows Zionism explicitly rejecting a religious project; “the Jewish people” are framed in secular terms, as an ethnic people. The Magen-David ✡︎ emerged as a symbol of ethnic Jewish identity at this same time, distinct from the seven-branch menorah which was the predominant symbol of Judaism as a religion in Europe. The use of this symbol on the flag of Israel underlines that Israel is a secular state, not a theocracy.

Second, the pointed use of the word “home” deliberately avoids identifying a sovereign Westphalian nation-state like Israel as it exists today as the defining goal of Zionism. Yes, that was the dream of many Zionists, but not all, and it was not the plan. Partly that reflects how at that time there was no imaginable path toward carving a new sovereign nation out of the vast Ottoman Empire which included Palestine. Partly that reflected how many leaders in the Zionist coalition actively rejected founding a nation-state as desirable at all. It is neither accidental nor incidental that this original definition of Zionism is at least compatible with a pluralistic society; many from both camps in the Zionist coalition rejected a vision of an exclusively Jewish society. (More on that in an earlier post on the origins and consequent meaning of “Zionism”.)

The Basel Program adopted by the 1897 Conference called for Zionist “settlements” in Palestine, and many key Zionist leaders did explicitly describe that project in terms modeled on the settler colonialism undertaken by the European colonial powers. But one should not misread this as plans for settlement simply paralleling European colonization of the Americas. Zionism could not conceive itself as an extension of the European colonial project since it was a response to oppression by those powers and had nothing like their capacities.

Instead, “settlment” took a form more comparable to the Pennsylvania Dutch, buying and homesteading land to create ethnic enclaves in territory under Ottoman governance. That is not to say that one should picture early Zionists as just like the pacifist Amish! Zionists created many enclaves on land purchased fair and square. And those enclaves were protected from hostile neighbors by Jewish militias which were hard to distinguish from other settlement militias which seized territory by force of arms, even terrorism. We must recognize both that brutality has been an integral part of the Zionist movement from the beginning and also that alternatives & opposition to brutality have equally deep roots in the movement.

Palestine before Israel

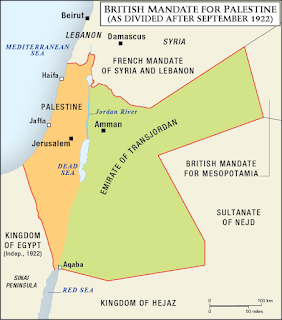

Again, in 1897 Palestine was the European name for a region within the much larger Ottoman Empire rather than a country with its own identity. Indeed, the first time someone called themself a “Palestinian” was the year after the First Zionist Conference. A map of “Palestine” would often include not just what is now Israel but also most of what is now Jordan; you can see an example at the top of this post.

The poetic resonance of Jews’ ancient roots in both history and myth was not the only reason Zionists chose Palestine as their site. There was a significant population of Jews already living among the Arab majority. And the weakness of the Ottoman Empire enabled local communities subject to relatively little government interference.

Indeed, the Ottoman Empire was so weak that it collapsed with WWI. Palestine became a colonial holding of the British Empire for the three decades which followed; they divided the region into the Emirate of Transjordan in the east (nominally independent but a “British protectorate”) and Mandatory Palestine (subject to direct British rule, which included a bit more than what is now Israel and its occupied territories) in the west.

Zionism was tolerated by both the Ottomans and British rather than sponsored by either of them, as reflected in the British government’s Balfour Declaration of 1917, which neither implied plans for a sovereign Jewish state nor subjected the British Empire to any binding commitments to the Zionist project:

His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

Meanwhile, the British did not even tolerate the growing Arab Palestinian nationalist movements of the era which were animated by frustration with British rule and by European Jewish immigration. Some of those movements sought independence for British Mandate Palestine as a new independent Arab state; others understood themselves as part of a broader pan-Arab nationalism which rejected dividing the Arab world into multiple states. In the late ’30s Palestinian nationalists’ armed revolt suffered British suppression with their characteristic brutality: colonialism, but neither settler colonialism nor Zionism.

Founding Israel

That in the wake of WWII the US & Europeans re-drew borders all over the world — that it would primarily be Britian who would adjudicate the competing claims of Jews and Arabs in Palestine — was not Zionist settler colonialism, but rather the legacy of European exploitative colonialism evolving into post-colonial imperialism.

By the late 1940s, there were an array of different Jewish populations in Palestine. There were non-Zionist Ashkenazi & Sephardic Jews whose ancestors had migrated there from Europe centuries before Zionism. There were Mizrahi Jews who looked just like their Arab neighbors, living in the same houses their great-great-grandparents had been born in under the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II in the 19th century. There were Jews born in houses their Zionist grandparents purchased at a fair price at the dawn of the 20th century. There were Jews born in houses stolen by Zionist militias in the 1920s. There were Jewish refugees who fled the Nazis in the 1930s. And there were growing numbers of Ashkenazi refugees, Shoah survivors who found that the Eastern Europeans who helped Nazis ship Jews to concentration camps were equally dangerous as administrators of Soviet domination, who had been turned away by the governments of the US and every nation in Europe, whose only hope for survival was the Zionists who brought them to Palestine to join their cause.

In 1947 & 1948, there were a series of partition proposals for Palestine sponsored by the then-new United Nations and others which framed a nation-state of Israel with boundaries very similar to what Israel would come to actually hold over the decades to come, plus Arab sovereignty over something close to what we now call the West Bank of the Jordan river, the Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip, and the state of Jordan.

From the British perspective, elevating the Emerite Of Transjordan into a truly independent state while converting most of British Mandate Palestine into the state of Israel was apportioning to the Arab majority most of the Palestinian territory the British Empire had controlled, with a smaller territory for Jews where they were already most numerous. The oddness of the Green Line map of Israel in these proposals partly emerges from the British Empire’s long habit of preserving their power by setting administrative borders which produced local conflicts.

These proposals were rejected by most Jews and practically all Arabs. The architects of what would become Israel wanted more land, while Arabs refused to accept Israel at all.

States in the region took shape not through negotiation but through bloodshed, in a tumultuous process between 1947-9. Israel emerged as a nation-state with borders very similar to the Green Line plan. Jordan eventually differed more from Transjordan under British rule, but not dramatically. The West Bank, the Golan Heights, and Gaza were never part of an independent state on the territory of British Mandate Palestine; Jordan, Syria, and Egypt absorbed them. I don’t have the expertise to untangle (much less summarize) this process well, not least because much of the history remains vigorously disputed by good faith scholars.

One can see why salty Israel apologists say that we already have a two-state solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict: Jordan & Israel. One can see why salty advocates for Palestinian liberation call Israel an illegitimate product of European colonialism. One can see why salty critics of pro-Palestinian movements ask why we hear so much about the oppression of Palestinian Arabs by Israel but never by Jordan, Egypt, and Syria (and more on that in a moment). All of these arguments are whataboutism but none of them are entirely bullshit.

Early Israel

One might very roughly parallel the founding of Israel with the partition of South Asia into India & Pakistan: border disputes, population transfers, local atrocities on all sides, and lasting instability.

Mizrahi Jews migrated to Israel from all over the Middle East, often (though not always) escaping severe oppression and deliberate efforts to displace them. In 1948 Holocaust refugees made Ashkenazim from Europe the majority of Jews in Israel; though Sephardic & Ashkenazi Jews continued to move to Israel from Europe and the US after ’48, there was so much migration by Mizrahim that they would become the majority of Jews in Israel … while they practically disappeared from the rest of the Middle East.

Israel apologists often sincerely believe that the 700,000+ Arab Palestinians who fled the newly-formed Israel departed “voluntarily” because the new Arab nations’ leaders directed Palestinians to clear a path for their armies’ attempts to destroy Israel. For a long time, the best available scholarship made that telling of history plausible, but in the last few decades it has become clear that this account was almost entirely a fabrication of Israeli propaganda. Zionist militias which evolved into Israel’s army murdered thousands to drive Arab Palestinians out; advocates for Palestinian liberation call this genocidal nightmare the Nakba, meaning “the catastrophe”. Arab states almost entirely refused to accept immigration by displaced Arab Palestinians because they believed doing so would legitimize Israel. Most refugees in the West Bank eventually became citizens of Jordan (as Jordan held the West Bank from 1950-1967) but many Palestinians displaced by Israel remained in legal limbo, stateless people living out the rest of their lives in refugee camps.

About 150,000 Arab Palestinians remained in Israel and became citizens … but second-class citizens subject to brutal military rule.

During this early era, Arab nations continued to refuse to recognize Israel’s legitimacy at all, declaring their plans to literally wipe the country from the map, as did the nationalist terrorists of the Palestine Liberation Organization founded in 1964.

During its first two decades, Israel fought a series of wars and border skirmishes with all of its neighbors. Israel hardliners describe these as unprovoked attacks by conquerer neighbors; historians find that Israel sometimes faced existential threats, while other times they were spoiling for a fight in hopes that they could seize more territory.

Echoes of this early era persist in the attitudes of all of the players in the region to this day. Many Israelis see themselves as still facing a constant threat of national destruction by an implacably hostile Arab world, with Arab Palestinians nothing other than the most intimate manifestation of that threat, despite Israel being far stronger than it was in its early era. Many Arabs still see Israel as nothing other than a final imposition of overt European imperialism and colonialism, despite the Mizrahi majority among Israeli Jews and decades of European animosity toward Israel.

The Six Day War, and occupation

In 1967, Israel fought the Six Day War with Jordan, Syria, and Egypt. At this point in this telling of the history, it should be evident why it is hard to say simply Who Started It.

Remember the West Bank of the Jordan River, the Gaza Strip, and the Golan Heights from British Mandate Palestine, which Jordan, Syria, and Egypt seized? Israel suffered ongoing rocket attacks and shelling from them, with the narrow segment between the Mediterranean Sea and the West Bank especially vulnerable, just a bit over nine miles wide at its tightest point. Israeli planners yearned to annex territory both for these strategic military reasons and as places for Israelis to live.

At the end of the 1967 war, these were now all in Israel’s hands … along with the Sinai Peninsula to the south, which had more than twice the area of all of pre-1967 Israel. In violation of international law and UN resolutions, Israel then subjected all of these territories to military occupation and built settlements for Jewish Israelis.

Israel would fight one last major war with its neighbors in 1973, retaining all of that land. After that Israel started emphatically denying that they had nuclear weapons … in a way that meant that they wanted everyone to know that they really had them. Border conflict never really stopped, but the full-scale wars ended.

Israel’s occupation of the Sinai did not last; under the Camp David Accords signed in 1979, Israel returned the Sinai to Egypt. (I confess to frustration that Israel’s critics somehow forget this when they insist that Israelis refuse to even consider any real sacrifices in pursuit of peace.)

Israel continued to lay claim to the Golan Heights to the north; the construction of settlements never stopped. Ongoing fighting over this territory — which has included Israel making military incursions into Syria & Lebanon beyond even the Golan — has a very complicated history, defined at least as much by internal strife in Syria & Lebanon as it is by fighting between those countries and Israel. That history may qualify as even more complicated than the history of Israel, and I confess that I do not understand it well enough to even attempt to summarize.

Within Israel’s pre-1967 borders, Israel lifted military rule over their Arab Palestinian citizens in 1966 so that theoretically they shared Jews’ rights protections under the law, democratic representation in government, et cetera. In practice Arab Palestinian citizens of Israel continued to suffer severe oppression. Today they account for about 2 million of Israel’s 9½ million citizens.

Oslo and afterward

(updated and expanded in late 2023 and after, to help contextualize the Hamas attack and Israel’s bloody response)

Gaza and the West Bank remained under Israeli military occupation; Israel continued to build settlements for a growing population of Jewish Israelis. In the late 1980s, vigorous nonviolent Palestinian protest & resistance known as the First Intifada made it clear that this was not sustainable.

In the early 1990s, “peace process” negotiations between Israeli and Palestinian leaders resulted in the Oslo Accords, an agreement which created the Palestinian Authority to govern both Gaza the West Bank. The PA is elected by Palestinian citizens of those territories, but the PA’s sovereignty is limited, with countless intrusions large and small by Israel. In the West Bank, the terms of Oslo allow for Israeli settlements under Israel’s control which break Palestinian territory into cantonized fragments; Israel populates those settlements with rightwing hardliner assholes prone to confronting their Palestinian neighbors with harassment and worse. Optimists hoped that Oslo would create an opening to further negotiation toward a more just resolution, but efforts which followed like Bill Clinton’s doomed 2000 attempt at Camp David foundered on distrust and hardliner intransigence on all sides.

Israel also had soldiers & settlers in Gaza after Oslo, but when the hard right Likud coalition won control of Israel’s government in 2005, they withdrew that presence. But conditions for Arab Palestinians in Gaza have actually been worse than in the West Bank. Israel’s military policing of Gaza from the outside is brutal, including a blockade of goods entering or leaving, a “buffer zone” which prevents cultivating much of the arable land, and hugely disproportionate reprisals by Israel’s military whenever radicals fire a rocket into Israel from Gaza, or even when Israel attributes a terrorist attack to Gazans. The common refrain that Gaza constitutes “an open-air prision” because of crowding and the brutality of these conditions is an exaggeration, but not much of one.

In a 2006 election, governance of the Palestinian Authority split between Gaza versus the West Bank. The corrupt, kleptocratic, secular Fatah party which sprung from the PLO retains power in the West Bank. The theocratic, authoritarian Hamas party overturned Fatah in Gaza; they have not permitted an election since.

During the post-Oslo era, radicals on all sides have violently sabotaged any movement toward reconciliation, peace, and justice. Optimism that relations might improve after Oslo was dashed by an Israeli hardliner assassinating prime minister Yitzhak Rabin for signing the Oslo Accords, followed by Palestinian terrorist attacks killing hundreds of Israeli civilians during the Second Intifada in the early 2000s. To advocates for Palestinian liberation, the Second Intifada was the inevitable, even justified, escalation of resistance to ongoing oppression. Many Jewish Israelis read the Second Intifada not as a demonstration that the post-Oslo order was unjust, but rather as a demonstration that concessions to Arab Palestinians only compromise Jews’ safety … which led to their support for the Likud political coalition which has tried to repress Arab Palestinians through more brutal military policing … which feeds Arab Palestinian support for violent resistance. Every softening of the conflict during this era has been cut short by provocations by one side or the other. The Likud coalition grew increasingly fascist, adding new incursions in the West Bank shrinking the archipeligo of territory in the West Bank under Palestinian control further and further.

A story in The New Yorker underlines the dynamics of this slow turn of the screw in the West Bank.

Kerry met regularly with Obama in the Oval Office. During one of those meetings, Kerry placed the maps on a large coffee table, one after another, so Obama and his advisers could study them. Ben Rhodes, one of Obama’s longest-serving advisers, said the President was shocked to see how “systematic” the Israelis had been at cutting off Palestinian population centers from one another. Lowenstein didn’t show the maps to the Israelis, but he did walk them through the key findings, which were incorporated into Kerry speeches and other documents. Lowenstein said the Israelis never challenged those findings.

Later, Kerry presented some of the maps to Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian President. Kerry’s goal was to show Abbas that the Obama Administration understood the extent to which the two-state solution was threatened. Abbas was taken aback. Instead of feeling reassured, he told a confidant that the maps convinced him that the Americans believed “the chances of a viable Palestinian state is next to nil.” Alarmed by Israeli actions depicted in the maps, Obama decided to abstain on a U.N. Security Council resolution condemning the settlements, clearing the way for its passage. It would be Obama’s final act of defiance against Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli Prime Minister, before Donald Trump took office and put in place policies that were far more accepting of the settlers.

Genocide in Gaza

That cycle continued until (and after) the horrifying Hamas attack on 7 October 2023 and Israel’s even more horrifying response.

It is absurd to accept Israel apologists’ claim that Israel’s Likud leadership seek only the release of Israeli hostages taken on 10/7. (We must also recognize how the return of hostages is an entirely reasonable demand; Hamas’ refusal demonstrates a callous disregard for Palestinian lives.) I also think that it is dangerously foolish to read Israel’s attack on Gaza as the realization of their dreams of eliminating Gaza’s Arab Palestinian population and annexing Gaza. I think the attack on Gaza is best understood as beginning as a panic response to distract Israelis from the Likud policy of endless military policing of Gaza & the West Bank failing to keep Israeli Jews safe, then quickly becoming an attempt to destroy Hamas and reconstruct Gaza into a form similar to the West Bank which would enable even more brutal military policing, using overwhelming military force which callously creates immense civilian casualties. For more detail about the dynamics of the 2023-4 crisis, I like this explainer.

We still must register that as genocidal: though not an attempt to eliminate Palestinians in Gaza, from the beginning it was an attack on the people of Gaza as a people, which has escalated as such efforts do.

And now we do have Trump & Netanyahu fantasizing about annexation.

The bottom line

Roughly a couple of million Arab Palestinians are oppressed by Israel in Gaza & the West Bank: increasingly brutal genocide in Gaza and ongoing displacement of Palestinians in the West Bank to build new settlements. Another couple of million Arab Palestinian citizens of Israel suffer significant oppression as well. Israel holds the unmistakable upper hand in an endless cycle of violence.

This emerges from — and continues to reflect — settler colonialism. This is unjust military occupation & policing and an unjust apartheid state. But students of American history should recognize from the particulars I have presented here how different they are from our horrors, so we should resist projecting our own patterns onto a very different situation.

If you have read this far, and come to wonder what “Zionism” means in a post-1948 and post-1967 world, I have an open letter to an anti-Zionist which may interest you. In short, “Zionism” means not support for Israel’s current border, political order, and policies; rather it means neither more nor less than support for the continued existence of the state of Israel — the only home which millions of people have ever known — in some form. It is important that we do not misrepresent what “Zionism” means.

More commentaries on settler colonialism

Tzvi Bisk’s liberal Zionist novel The Suicide of the Jews offers a tidy summation of how Zionists tend to rationalize their project as distinct from the history of colonialism. Each of these points offers apologetics neither simply true nor simply false. Criticisms of Israel & Zionism should grapple with these peculiarities.

-

Every colonial enterprise represented or derived from an existing mother country or group of countries — Zionism did not.

-

No other colonial enterprise viewed itself as returning to its homeland — Zionism did.

-

No other modern colonial enterprise was driven by the desire of the colonizers to escape persecution and discrimination — Zionism was.

-

No other colonial enterprise viewed its colonial ambition as being part and parcel of their national cultural, psychological and moral renewal — Zionism did.

-

No other colonial enterprise satisfied itself with only one colony — Zionism did.

-

No other colonial enterprise desired so passionately to settle a land devoid of natural resources — Zionism did.

-

No other colonial enterprise desired to create an independent state (all the others saw themselves as dependent colonies of the mother country) — Zionism did.

-

No other colonial enterprise desired to create an entirely new society — Zionism did.

But Ha’Aretz offers the article

Israel Is a Settler Colonial State — and That’s OK addressing some of the deceits of Bisk’s list and defending the framework of “settler colonialism” as a necessary goad to a more just future for Israel.

In fact, rigorous scholars who study the applicability of the settler colonial framework for the history of Israel / Palestine need not subscribe to a political agenda committed to the end of the State of Israel. Moreover, claiming that structurally, Zionist settlers are comparable to American pioneers or South African Voortrekkers, does not necessitate the denial of a historical connection between Jews and the Holy Land, the unique nature of European anti-Semitism, or even requires having sympathy for the Palestinian armed struggle against Zionism. As a matter of fact, even prominent Zionists made explicit comparisons between their own political movement and those of settlers around the world.

The indispensible Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg has a long, instructive post about double-edged particulars which make Israel unique among colonial projects:

Jews have not been part of colonial projects in the same way that colonizing nations have.

But we have been, often, part of them. It’s all both / and.

Often, Jews have been simultaneously settlers and refugees.

[⋯]

Jews generally did not leave the places we were living in order to steal, but rather: we were seeking safety.

And yet: Jews benefitted mightily from that exploitation, extraction, destruction and land theft.

There’s a difference between a major European power’s relationship to colonialism and Jewish refugee’s.

But the Jewish refugee is nonetheless participating in colonialism.

I highly recommend clicking through to read the whole thing.

And if you want even more, I have a later post with a grab bag of links & quotes further expanding on many of the particulars.